Glee’s season one finale didn’t prepare me for this.

As someone who often finds comfort through guilty-pleasure television, it warms my heart to see that a more realistic depiction of sexuality is trending on TV. Young people today are growing up in the age of Sex Education and The Sex Lives of College Girls–shows that not only highlight the importance of sex positivity and reproductive healthcare but actively works to portray these themes as part of everyday life. The closest I had to this growing up was Glee’s season one finale, where a softcore birth sequence was spliced together by the rival show choir’s performance of “Bohemian Rhapsody”.

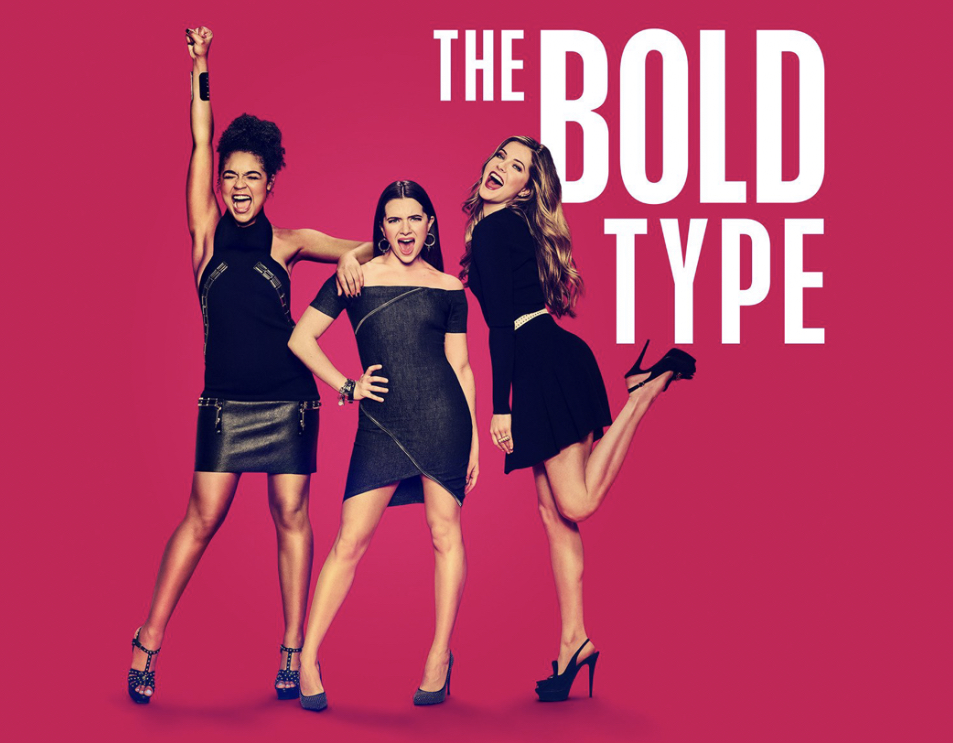

One of the best shows to come out in the past five years that follows this same trend is Freeform’s The Bold Type, which ended after five seasons earlier this year. The Bold Type follows three best friends who each fight to have a voice within their own fields. It has consistently been praised for portraying the lives of working women with a heavier dose of reality than most other workplace dramedies attempt.

Among its litany of carefully constructed story-lines aimed at expanding what is represented on mainstream television, The Bold Type is no stranger to showcasing the trials that come with seeking out necessary reproductive healthcare. In the show’s first season, Jane (Katie Stevens), the plucky, yet, admittedly, kind of White Feminist writer, tests positive for the BRCA mutation and makes the decision to freeze her eggs. In season two, Kat (Aisha Dee), Scarlet Magazine’s radical activist Social Media Director, has her abortion outed by an unnamed man who disliked one of her posts criticizing a male-dominated industry. However, the show abruptly ended its campaign of showcasing different aspects of reproductive health issues after the season four episode where Sutton (Meghann Fahy) has a miscarriage.

Pregnancy loss is one of those fun, taboo-adjacent parts of the feminine experience that fails to land on mainstream media. After my miscarriage a few months ago, I delved into the deep recesses of streaming services to try and find any show or any movie that touched on this issue – maybe it was because I needed to see someone else going through what I went through, maybe it was some latent form of sado-masochism, who knows (that’s a conversation to be had with my therapist at a later date). When I remembered that The Bold Type had an entire episode dedicated to Sutton’s miscarriage, I immediately went back to rewatch – and was left feeling disappointed and even more isolated because of how utterly misinformed the show runners seemed when working on this episode.

It took Sutton’s doctor twenty-seven seconds to perform an ultrasound and tell her she was having a miscarriage. The whole appointment ran just under two minutes. At the risk of nit-picking, my eight-hour emergency room visit did begin with my doctor telling me about my miscarriage in a sequence of three short sentences that informed me of my pregnancy loss before technically informing me of my pregnancy. This is where the similarities came to an abrupt end.

I had the remaining seven hours and fifty minutes, punctuated by an emergency dilation and curettage procedure and some very fun anti-anxiety medication, to begin to process what had happened to my body. Had the writers offered more than the initial Two-Minute Miscarriage Sequence, audiences would have had time to sit in the gravity of Sutton’s situation before being thrust into a scene showing her back at work with her life seemingly unbothered by what her body was going through.

After telling Sutton that there was no heartbeat on the ultrasound, the doctor tells her that ten percent of pregnancies end in miscarriage. Given how rare pregnancy loss is in modern media, portraying it in an oversimplification feels nothing short of disappointing.

Data collection on pregnancy loss is incredibly difficult. There are too many variables at play to condense miscarriages into a simple ten percent statistic, especially when one takes into consideration the miscarriages that happen outside of hospital settings, or the ones that happen so early on that a woman doesn’t know she’s pregnant at all. The one in ten figure is misleading at best, with a much more realistic number being one in five.

On normal diagnosis, women are given three options: waiting to bleed, medication to bring on the bleeding, or a medical procedure to complete the process. Each has specific challenges, but ultimately it should be a woman’s choice which is the least confronting of the three. No options were offered to Sutton. Not even to mention the suggestion of a follow-up appointment to ensure she wouldn’t develop a life-threatening infection (speaking as someone whose miscarriage did end in said life-threatening infection, a choice would have been nice).

What follows in the episode would have been much more poignant had Sutton been advised to seek out professional care after her miscarriage. She immediately realizes that she doesn’t want children, which sparks the dissolution of her marriage. Had the option for counseling (something that is repeatedly highlighted by medical and sociological research following pregnancy loss) even been offered to her in this episode, her decisions would have felt less like the beginning of her character’s downward spiral and more like a personal choice that she made for herself after the incredible trauma brought on by this experience.

Several times during the episode, she’s told that the miscarriage wasn’t her fault – despite never articulating this fear. Sutton has her best friends and her unreasonably handsome husband telling her how she should feel or act. The only mention of how Sutton feels about what has happened to her is at the very end of the episode, where she shares the relief she feels for not having a child. While this is great representation of a non-conventional reaction to pregnancy loss, it’s the last we hear of the topic. The episode ends and divorce proceedings seemingly begin.

We never see the aftermath. There’s no implication of the prolonged, unnerving sense of feeling like one’s relationship with their own body has been irreparably fucked. Sutton had her friends and her husband supporting her emotionally, but we never saw them taking care of her while she was recovering (God bless my incredibly patient former partner for having to see how gross my recovery was and still taking care of me in spite of it). While neither Sutton or myself wanted the pregnancies that we lost, there is nothing there that shows the severely jarring feelings that come from grieving something you know you couldn’t have.

Essentially, Sutton’s miscarriage was used as a catalyst to spark the end of an already on-again-off-again relationship. While there is something to be said about leaving out the gory details for the sake of digestible storytelling, what we were given was an inadequate way of portraying something so serious. Pregnancy loss is a traumatic, invasive, and horrifically intimate thing that happens to countless women. Tying a story like this up in a neat, forty-five minute bow only neglects the reality of the situation and inadvertently isolates audiences whose experiences aren’t perfectly aligned.

I’m constantly moved by Carter’s honest and striking voice; she finds the perfect wording that we’ve been looking for. I get the strong feeling Challen will be/is one of the next profound storytellers to change the reproductive narrative in media. So so much love for Challen!!